Substance in a refrigeration cycle

|

|

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all important aspects of the article. (March 2021)

|

A DuPont R-134a refrigerant

A DuPont R-134a refrigerant

A refrigerant is a working fluid used in cooling, heating or reverse cooling and heating of air conditioning systems and heat pumps where they undergo a repeated phase transition from a liquid to a gas and back again. Refrigerants are heavily regulated because of their toxicity and flammability[1] and the contribution of CFC and HCFC refrigerants to ozone depletion[2] and that of HFC refrigerants to climate change.[3]

Refrigerants are used in a direct expansion (DX- Direct Expansion) system (circulating system)to transfer energy from one environment to another, typically from inside a building to outside (or vice versa) commonly known as an air conditioner cooling only or cooling & heating reverse DX system or heat pump a heating only DX cycle. Refrigerants can carry 10 times more energy per kg than water, and 50 times more than air.

Refrigerants are controlled substances and classified by International safety regulations ISO 817/5149, AHRAE 34/15 & BS EN 378 due to high pressures (700–1,000 kPa (100–150 psi)), extreme temperatures (−50 °C [−58 °F] to over 100 °C [212 °F]), flammability (A1 class non-flammable, A2/A2L class flammable and A3 class extremely flammable/explosive) and toxicity (B1-low, B2-medium & B3-high). The regulations relate to situations when these refrigerants are released into the atmosphere in the event of an accidental leak not while circulated.

Refrigerants (controlled substances) must only be handled by qualified/certified engineers for the relevant classes (in the UK, C&G 2079 for A1-class and C&G 6187-2 for A2/A2L & A3-class refrigerants).

Refrigerants (A1 class only) Due to their non-flammability, A1 class non-flammability, non-explosivity, and non-toxicity, non-explosivity they have been used in open systems (consumed when used) like fire extinguishers, inhalers, computer rooms fire extinguishing and insulation, etc.) since 1928.

History

[edit]

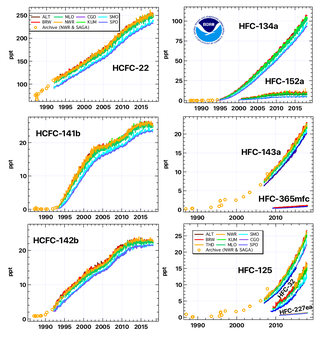

The observed stabilization of HCFC concentrations (left graphs) and the growth of HFCs (right graphs) in earth's atmosphere.

The observed stabilization of HCFC concentrations (left graphs) and the growth of HFCs (right graphs) in earth's atmosphere.

The first air conditioners and refrigerators employed toxic or flammable gases, such as ammonia, sulfur dioxide, methyl chloride, or propane, that could result in fatal accidents when they leaked.[4]

In 1928 Thomas Midgley Jr. created the first non-flammable, non-toxic chlorofluorocarbon gas, Freon (R-12). The name is a trademark name owned by DuPont (now Chemours) for any chlorofluorocarbon (CFC), hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC), or hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) refrigerant. Following the discovery of better synthesis methods, CFCs such as R-11,[5] R-12,[6] R-123[5] and R-502[7] dominated the market.

Phasing out of CFCs

[edit]

See also: Montreal Protocol

In the mid-1970s, scientists discovered that CFCs were causing major damage to the ozone layer that protects the earth from ultraviolet radiation, and to the ozone holes over polar regions.[8][9] This led to the signing of the Montreal Protocol in 1987 which aimed to phase out CFCs and HCFC[10] but did not address the contributions that HFCs made to climate change. The adoption of HCFCs such as R-22,[11][12][13] and R-123[5] was accelerated and so were used in most U.S. homes in air conditioners and in chillers[14] from the 1980s as they have a dramatically lower Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP) than CFCs, but their ODP was still not zero which led to their eventual phase-out.

Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) such as R-134a,[15][16] R-407A,[17] R-407C,[18] R-404A,[7] R-410A[19] (a 50/50 blend of R-125/R-32) and R-507[20][21] were promoted as replacements for CFCs and HCFCs in the 1990s and 2000s. HFCs were not ozone-depleting but did have global warming potentials (GWPs) thousands of times greater than CO2 with atmospheric lifetimes that can extend for decades. This in turn, starting from the 2010s, led to the adoption in new equipment of Hydrocarbon and HFO (hydrofluoroolefin) refrigerants R-32,[22] R-290,[23] R-600a,[23] R-454B,[24] R-1234yf,[25][26] R-514A,[27] R-744 (CO2),[28] R-1234ze(E)[29] and R-1233zd(E),[30] which have both an ODP of zero and a lower GWP. Hydrocarbons and CO2 are sometimes called natural refrigerants because they can be found in nature.

The environmental organization Greenpeace provided funding to a former East German refrigerator company to research alternative ozone- and climate-safe refrigerants in 1992. The company developed a hydrocarbon mixture of propane and isobutane, or pure isobutane,[31] called "Greenfreeze", but as a condition of the contract with Greenpeace could not patent the technology, which led to widespread adoption by other firms.[32][33][34] Policy and political influence by corporate executives resisted change however,[35][36] citing the flammability and explosive properties of the refrigerants,[37] and DuPont together with other companies blocked them in the U.S. with the U.S. EPA.[38][39]

Beginning on 14 November 1994, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency restricted the sale, possession and use of refrigerants to only licensed technicians, per rules under sections 608 and 609 of the Clean Air Act.[40] In 1995, Germany made CFC refrigerators illegal.[41]

In 1996 Eurammon, a European non-profit initiative for natural refrigerants, was established and comprises European companies, institutions, and industry experts.[42][43][44]

In 1997, FCs and HFCs were included in the Kyoto Protocol to the Framework Convention on Climate Change.

In 2000 in the UK, the Ozone Regulations[45] came into force which banned the use of ozone-depleting HCFC refrigerants such as R22 in new systems. The Regulation banned the use of R22 as a "top-up" fluid for maintenance from 2010 for virgin fluid and from 2015 for recycled fluid.[citation needed]

Addressing greenhouse gases

[edit]

With growing interest in natural refrigerants as alternatives to synthetic refrigerants such as CFCs, HCFCs and HFCs, in 2004, Greenpeace worked with multinational corporations like Coca-Cola and Unilever, and later Pepsico and others, to create a corporate coalition called Refrigerants Naturally!.[41][46] Four years later, Ben & Jerry's of Unilever and General Electric began to take steps to support production and use in the U.S.[47] It is estimated that almost 75 percent of the refrigeration and air conditioning sector has the potential to be converted to natural refrigerants.[48]

In 2006, the EU adopted a Regulation on fluorinated greenhouse gases (FCs and HFCs) to encourage to transition to natural refrigerants (such as hydrocarbons). It was reported in 2010 that some refrigerants are being used as recreational drugs, leading to an extremely dangerous phenomenon known as inhalant abuse.[49]

From 2011 the European Union started to phase out refrigerants with a global warming potential (GWP) of more than 150 in automotive air conditioning (GWP = 100-year warming potential of one kilogram of a gas relative to one kilogram of CO2) such as the refrigerant HFC-134a (known as R-134a in North America) which has a GWP of 1526.[50] In the same year the EPA decided in favour of the ozone- and climate-safe refrigerant for U.S. manufacture.[32][51][52]

A 2018 study by the nonprofit organization "Drawdown" put proper refrigerant management and disposal at the very top of the list of climate impact solutions, with an impact equivalent to eliminating over 17 years of US carbon dioxide emissions.[53]

In 2019 it was estimated that CFCs, HCFCs, and HFCs were responsible for about 10% of direct radiative forcing from all long-lived anthropogenic greenhouse gases.[54] and in the same year the UNEP published new voluntary guidelines,[55] however many countries have not yet ratified the Kigali Amendment.

From early 2020 HFCs (including R-404A, R-134a and R-410A) are being superseded: Residential air-conditioning systems and heat pumps are increasingly using R-32. This still has a GWP of more than 600. Progressive devices use refrigerants with almost no climate impact, namely R-290 (propane), R-600a (isobutane) or R-1234yf (less flammable, in cars). In commercial refrigeration also CO2 (R-744) can be used.

Requirements and desirable properties

[edit]

A refrigerant needs to have: a boiling point that is somewhat below the target temperature (although boiling point can be adjusted by adjusting the pressure appropriately), a high heat of vaporization, a moderate density in liquid form, a relatively high density in gaseous form (which can also be adjusted by setting pressure appropriately), and a high critical temperature. Working pressures should ideally be containable by copper tubing, a commonly available material. Extremely high pressures should be avoided.[citation needed]

The ideal refrigerant would be: non-corrosive, non-toxic, non-flammable, with no ozone depletion and global warming potential. It should preferably be natural with well-studied and low environmental impact. Newer refrigerants address the issue of the damage that CFCs caused to the ozone layer and the contribution that HCFCs make to climate change, but some do raise issues relating to toxicity and/or flammability.[56]

Common refrigerants

[edit]

Refrigerants with very low climate impact

[edit]

With increasing regulations, refrigerants with a very low global warming potential are expected to play a dominant role in the 21st century,[57] in particular, R-290 and R-1234yf. Starting from almost no market share in 2018,[58] low GWPO devices are gaining market share in 2022.

| Code |

Chemical |

Name |

GWP 20yr[59] |

GWP 100yr[59] |

Status |

Commentary |

| R-290 |

C3H8 |

Propane |

|

3.3[60] |

Increasing use |

Low cost, widely available and efficient. They also have zero ozone depletion potential. Despite their flammability, they are increasingly used in domestic refrigerators and heat pumps. In 2010, about one-third of all household refrigerators and freezers manufactured globally used isobutane or an isobutane/propane blend, and this was expected to increase to 75% by 2020.[61] |

| R-600a |

HC(CH3)3 |

Isobutane |

|

3.3 |

Widely used |

See R-290. |

| R-717 |

NH3 |

Ammonia |

0 |

0[62] |

Widely used |

Commonly used before the popularisation of CFCs, it is again being considered but does suffer from the disadvantage of toxicity, and it requires corrosion-resistant components, which restricts its domestic and small-scale use. Anhydrous ammonia is widely used in industrial refrigeration applications and hockey rinks because of its high energy efficiency and low cost. |

| R-1234yf HFO-1234yf |

C3H2F4 |

2,3,3,3-Tetrafluoropropene |

|

<1 |

|

Less performance but also less flammable than R-290.[57] GM announced that it would start using "hydro-fluoro olefin", HFO-1234yf, in all of its brands by 2013.[63] |

| R-744 |

CO2 |

Carbon dioxide |

1 |

1 |

In use |

Was used as a refrigerant prior to the discovery of CFCs (this was also the case for propane)[4] and now having a renaissance due to it being non-ozone depleting, non-toxic and non-flammable. It may become the working fluid of choice to replace current HFCs in cars, supermarkets, and heat pumps. Coca-Cola has fielded CO2-based beverage coolers and the U.S. Army is considering CO2 refrigeration.[64][65] Due to the need to operate at pressures of up to 130 bars (1,900 psi; 13,000 kPa), CO2 systems require highly resistant components, however these have already been developed for mass production in many sectors. |

Most used

[edit]

| Code |

Chemical |

Name |

Global warming potential 20yr[59] |

GWP 100yr[59] |

Status |

Commentary |

| R-32 HFC-32 |

CH2F2 |

Difluoromethane |

2430 |

677 |

Widely used |

Promoted as climate-friendly substitute for R-134a and R-410A, but still with high climate impact. Has excellent heat transfer and pressure drop performance, both in condensation and vaporisation.[66] It has an atmospheric lifetime of nearly 5 years.[67] Currently used in residential and commercial air-conditioners and heat pumps. |

| R-134a HFC-134a |

CH2FCF3 |

1,1,1,2-Tetrafluoroethane |

3790 |

1550 |

Widely used |

Most used in 2020 for hydronic heat pumps in Europe and the United States in spite of high GWP.[58] Commonly used in automotive air conditioners prior to phase out which began in 2012. |

| R-410A |

|

50% R-32 / 50% R-125 (pentafluoroethane) |

Between 2430 (R-32) and 6350 (R-125) |

> 677 |

Widely Used |

Most used in split heat pumps / AC by 2018. Almost 100% share in the USA.[58] Being phased out in the US starting in 2022.[68][69] |

Banned / Phased out

[edit]

| Code |

Chemical |

Name |

Global warming potential 20yr[59] |

GWP 100yr[59] |

Status |

Commentary |

| R-11 CFC-11 |

CCl3F |

Trichlorofluoromethane |

6900 |

4660 |

Banned |

Production was banned in developed countries by Montreal Protocol in 1996 |

| R-12 CFC-12 |

CCl2F2 |

Dichlorodifluoromethane |

10800 |

10200 |

Banned |

Also known as Freon, a widely used chlorofluorocarbon halomethane (CFC). Production was banned in developed countries by Montreal Protocol in 1996, and in developing countries (article 5 countries) in 2010.[70] |

| R-22 HCFC-22 |

CHClF2 |

Chlorodifluoromethane |

5280 |

1760 |

Being phased out |

A widely used hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC) and powerful greenhouse gas with a GWP equal to 1810. Worldwide production of R-22 in 2008 was about 800 Gg per year, up from about 450 Gg per year in 1998. R-438A (MO-99) is a R-22 replacement.[71] |

| R-123 HCFC-123 |

CHCl2CF3 |

2,2-Dichloro-1,1,1-trifluoroethane |

292 |

79 |

US phase-out |

Used in large tonnage centrifugal chiller applications. All U.S. production and import of virgin HCFCs will be phased out by 2030, with limited exceptions.[72] R-123 refrigerant was used to retrofit some chiller that used R-11 refrigerant Trichlorofluoromethane. The production of R-11 was banned in developed countries by Montreal Protocol in 1996.[73] |

Other

[edit]

| Code |

Chemical |

Name |

Global warming potential 20yr[59] |

GWP 100yr[59] |

Commentary |

| R-152a HFC-152a |

CH3CHF2 |

1,1-Difluoroethane |

506 |

138 |

As a compressed air duster |

| R-407C |

|

Mixture of difluoromethane and pentafluoroethane and 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane |

|

|

A mixture of R-32, R-125, and R-134a |

| R-454B |

|

Difluoromethane and 2,3,3,3-Tetrafluoropropene |

|

|

HFOs blend of refrigerants Difluoromethane (R-32) and 2,3,3,3-Tetrafluoropropene (R-1234yf).[74][75][76][77] |

| R-513A |

|

An HFO/HFC blend (56% R-1234yf/44%R-134a) |

|

|

May replace R-134a as an interim alternative[78] |

| R-514A |

|

HFO-1336mzz-Z/trans-1,2- dichloroethylene (t-DCE) |

|

|

An hydrofluoroolefin (HFO)-based refrigerant to replace R-123 in low pressure centrifugal chillers for commercial and industrial applications.[79][80] |

Refrigerant reclamation and disposal

[edit]